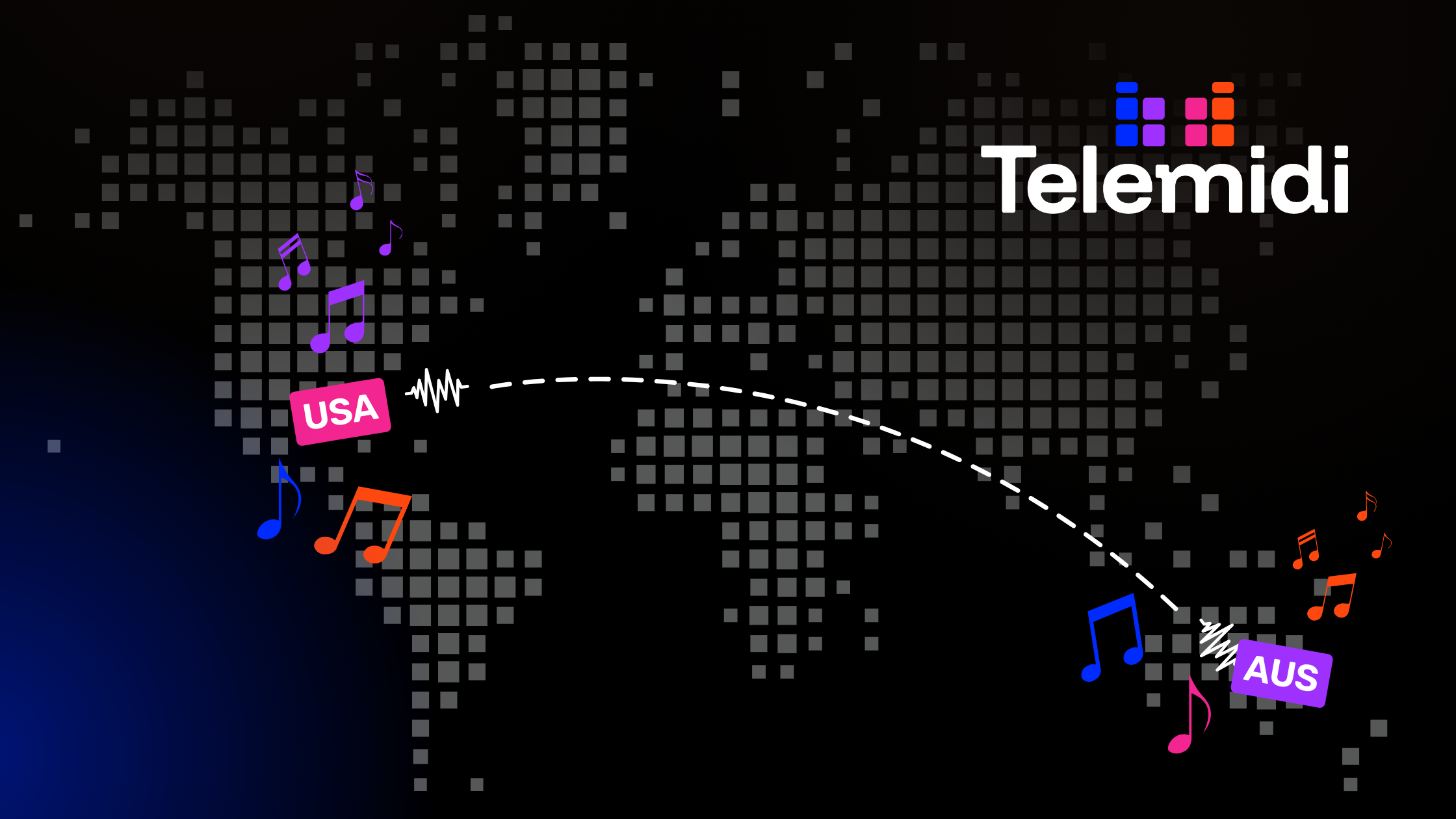

In May 2025, Telemidi reached a defining milestone: its first real-time musical connection with the United States. The session, linking remote Alice Springs (Australia) and New Orleans (USA), marked a symbolic moment of musical, cultural and technical convergence. Special thanks to Travis Simmons and Jordan Bush for facilitating the trial, where musicians from two continents shared musical gestures across vast distance using synchronised pulse and responsive listening. It was not a concert; it was simply a test. But, like the earliest telegraph cables across the Atlantic, it proved something monumental: that presence, pulse, and musical trust can be achieved remotely.

1. Remote Pulse and Digital Co-Regulation

Eliminating latency is impossible, so Telemidi works with it, by emphasising coordinated rhythmic relationships through a shared musical pulse, the fluid exchange of collaborator’s intentions, and an ongoing iteration of musical phrase structures. The Alice–New Orleans test demonstrated that with standard network conditions, performers could sustain continuous rhythmic and harmonic exchange. It was simply awesome. These sessions often rely on repeating looped phrase structures that could be modified with small gestures, to enable musical interactions across vast geographical distances. This is supported by Pressing’s (2002) argument that periodicity and repetition act as a ‘temporal scaffolding’ for collective musical emergence (Pressing, 1993).

2. Cultural Transparency in Remote Collaboration

The Telemidi PhD research revealed that musical ideas arrive with artefacts of the systems through which they pass, highlighting how each performer’s sound reflects both personal and technical environments. In TMP settings, tone colour, articulation, and rhythmic feel are shaped by the performer’s interface, system setup, and location. In the Alice–New Orleans test, these artefacts became part of the musical dialogue, but were kept in check by the Telemidi system, so that the nuance of New Orleans harmonic and rhythmic progressions could be immediately felt half a world away. The interaction between players created a responsive system of exchange, where clarity of phrase, rhythmic grounding, and mutual listening emerged through a responsive system that allowed musical gestures to be adjusted and refined across distance. Ascott’s view of networking as ‘a field of reciprocal transformation’ affirms this decentralised artistic dynamic (Ascott, 1984).

3. Adaptability Across Network Contexts

In previous sessions such as the Rwanda–Canada trial, performers adapted their strategies using rhythmic anticipation, and a flexibility of timing when listening to incoming performance data that had been altered by the Internet network itself. By contrast, the Alice–New Orleans connection functioned under improved network conditions, allowing tempo-sensitive materials to pass fluidly between nodes. Telemidi adapts within constraints, treating variation as an input to the performance rather than an interruption. Bell’s historical insights into the dislocation of musical time through recording, are challenged by Telemidi’s re-centring of co-located temporal experience (Bell, 2015). Oliveros et al. (2009) reinforce the importance of cultivating attention in telematic spaces, with Oliveros stating: “communicating sound over distance has been important to humans (and animals) for all kinds of purposes” (Oliveros et al., 2009, p. 96).

4. Towards Cross-Cultural Musical Design

Telemidi’s architecture supports diverse instruments, genres, and styles without assuming a single sonic or notational standard. Once remote collaborators engage in Telemidi’s system, rhythm becomes the shared denominator, particularly where the expectations of instrumentation and genre variations exist. Rather than defaulting to Western music theory conventions, the system embraces performance ecologies that include looping devices, groove-based practices, and embodied timing strategies that are more common and pertinent in the globalised production of modern popular music. Diduck’s (2015) critique of claviocentrism underscores the importance of alternative control paradigms, noting how

keyboard-centric design reinforces certain musical hierarchies. As Strachan (2017) reminds us, technologies of music are inseparable from identity politics and “as musicians’ interface with them, they shape and are shaped by them” (Strachan, 2017, p. 66).

Conclusion

What began as a test became a landmark: a demonstration of how musical connection can thrive across distance through rhythm, listening, and shared intention. The Alice Springs–New Orleans session did not erase cultural or geographic difference, it honoured it. Telemidi continues to develop as a system designed not to eliminate space, but to animate it with musical presence. In doing so, it repositions remote collaboration not as a compromise, but as a unique mode of co-creation. The direct implications of this result, will be announced in the near future as Telemidi steps up to deliver a range of musical, social, cultural and health benefits to participants in ongoing remote musical collaborations. Please stay tuned for this exciting next chapter.